|

"ICICLES."

PETERSON'S MAGAZINE. FEBRUARY, 1862

|

||

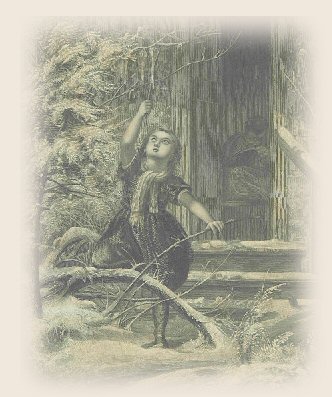

| "Oh, mamma! see! see! the first icicles!

They are all over the little tree I planted! I am so glad it snowed last night!

Ain't they beautiful? When the sun shines see how many colors, and how they

glisten, and the white, white snow makes them still prettier. May I go out and

get one, just one? I can reach them so nicely on the little tree!" and, without

waiting for an answer, the child hastily tied at scarf around her neck and ran

out on the snow covered steps. Like most earthly treasures hers were too high to

grasp, and the long stick she used to knock the pretty treasures down, only

served to shatter them to atoms at her feet, till a call from her mother

reminded her that open doors in winter did not warm kitchens, and she came in.

"After all they would melt in here," she said, going to her old place at the window, "and they look just as pretty from inside." And that one sentence was the key-note to little Bertha Schwindanís heart. She was a German child, with soft, sunny hair and deep blue eyes; and while she could look back on baby recollections of her native land and her fatherís care, she could still take bright view of the new home, the narrow means, and toilsome life which followed emigration, and her fatherís death. Gustavus Schwindan was one of that ill-fated class, a genius! From early boyhood music had been his goddess, to be worshiped, courted, at any cost, and all seasons. In his own country he had not prospered. A situation as second violinist in a mammoth orchestra had afforded sufficient income for his bachelor life; but when he married, he determined to cross the wide ocean and tempt fortune in a new clime. Little Bertha was six years old before this pet scheme was carried out; and before she saw her seventh birthday the sods of America lay heavy on her fatherís breast, and her mother, a stranger in a strange land, turned her footsteps to the West, the land of promise. Kind hearts had seen the gentle widow, and remembered the gifted musician, and a subscription was raised in the new land to aid the patient stranger. It was a narrow house, ill-furnished, in a sparsely populated spot, where Gertrude Schwindan found her home; but the few neighbors spoke in the tongue of the Fatherland, her childís heart was light, and her voice glad on the free, open country: there was a promise of work, and she was content so to live. One room in the little cottage was tenanted by its owner, and he gave Gertrude the rest, free, for the simple repast which he shared with her and Bertha. He was a man of some forty years of age, with a hard, stern face, not a German, though the language came easily from his lips. And while Bertha, with bright eyes and glowing cheeks, looked lovingly and admiringly on the lovely winterís prospect, this manís eyes were fixed upon it from his window, and his heart was full of bitterness as he murmured, "Icicles! Cold, bleak, desolate! Fair and smooth as a womenís face, cold and hard as her heart! Glistening as her false smile, beautiful afar off, chilling if grasped! Oh! where can I turn that all will not remind me of the past? I have left home and friends, the crowded and the lovely country-seats where we were together, to busy myself here, among new faces in a wild spot, only to find memory more busy in loneliness, imagination more ready to find smiles in every site and sound. My books weary me, my thoughts madden me. Where can I find rest?" "Mr. William! Mother says breakfast is ready." Ah! Is it you, little Icicles?" said he, giving her a nick-name, from the occupation at which he had just seen her. " Come in!" She entered and stood demurely before him. "Are you not sorry," he said, gently, though no smile came on his face, "are you not sorry that winter has come? The ground is covered with snow, and the air is bitterly cold, You cannot run out, and all the pretty flowers are gone!" "But mamma says they are only sleeping under the pretty white snow, to waken up again in spring time." "But you?" "Oh! I can run out for a little while, and then come in to sew, or try to find out what the funny English letters stand for. Mamma says I must learn to talk and read too in English now but I donít get along very fast. Wilhelm, the old carpenter, helps me; but it is so far to walk, and he is so often busy." "Then the winter days are long," said Mr. William. "I can learn more and help mamma more." "You, little one! What can you do?" "I can bring in the wood from the shed, and run for the dishes, and sweep up the hearth, and call you when meals are ready - and oh, dear! What will mamma say? Your coffee will be cold, because I stay here chattering so long." "Gertrude," said Mr. William, as he sat down to the breakfast-table, "Bertha is old enough now to study regularly." "Yes, almost eight!" sighed Gertrude. "Let her come to me from nine to one every morning, and I will attend to her studies. It is not necessary," he added, as Gertrude began her eager thanks, "I have more time than I can use," and he sighed heavily. The Germans learned to wonder at Berthaís love for the cold, grave American, whose stern face never relaxed, and whose step was so slow and heavy; but in the morning hours of study the child could win gentle words, and though rarely, a smile which lighted the stern face like sunshine. She little guessed her power. Inter a heart made desolate by a false love, an unworthy friend, and broken trusts, her childish happiness, her loving disposition, and rare intellectual gifts, had entered like a new life. He read on the broad, white brow the genius her father left as his legacy; while in the sensitive mouth, the clear blue eye and low-toned voice, he saw again her motherís

|

gentleness

and pure faith; and little "Icicles," as he loved to call her, became

pupil, companion, friend to the weary, heart-sick man, whose face

brightened for her alone, whose rare smile was her choicest reward for

patient study. Nine years later, and looking upon Bertha Schwindan, where

shall we find her? Not in her old Western home, but in a lovely cottage

some ten miles out from New York, where Mr. William had placed her and her

mother, previous to his own departure of Europe. For nine years he had

made her life happy, by opening before her eager mind new paths of

knowledge to be explored, training her ready fingers over the ivory keys

of the piano he procured for her , and urging her daily to new efforts.

Neither Bertha nor her mother could tell when they first learned to look

upon him as their guardian and friend; but the little cottage brightened

with his gifts, and work flowed in for busy fingers, at his suggestion,

among the richer neighbors; and now, in their new home, Gertrude had found

the savings of the past years well invested for her use, and Bertha, in a

farewell letter, learned that she was independent of work. Friends soon came to call upon the German lady and that "beautiful blonde," her daughter. The new neighbor was pronounced lady-like, the home comme il faut, and the German girl an acquisition to the parties, and Bertha found herself "in society" without an effort. And he, the guardian and teacher of her childhood, the beloved instructor and friend, where was he? Far away on the bounding Atlantic, trying to still a new tumult in his weary heart. His child had become a woman; and he loved her! All the coldness of his heart which she had thawed, in her winning childhood, gathered there again when he left her. He dared not tell her of his love, for she was a child yet in her innocence of all worldly forms, all society; and her secluded life was too recent to trust her, to let its love be lasting when she left it. So, to try his darling, to see if the pure heart could resist the glittering temptations of the world, he placed her in her new home where his name was known, and his introduction opened to her the dazzling mazes of fashionable life, in which his generosity gave her the means of shining; and then, unable to stand by and see perhaps another win his treasure, he left her, again to resume his lonely life and try once more to forget a past. Look in upon a parlor, small it is true, but furnished with every elegant appointment which taste could suggest or money supply. Two years has it been the home of Gertrude Schwindan and her daughter. The piano stands open, with choice music scattered carelessly over it, and the center-table is covered with books and work. Gertrude, still lovely with her gentle face and graceful figure, is bending over her embroidery; but Bertha will touch nothing. Up and down with quick steps she paces the little parlor. Her tall, graceful figure in its dark silk shows health and freedom in every motion; her rich profusion of light hair shades with its glossy braids a face full of high intellect and of rare beauty. Some one comes softly to the door of the next room, sets t ajar, and, unseen, retires: but Bertha still keeps up her hasty, troubled walk. "Mother, did you here Mr. James describing the new house that has been built on the site of our little cot, our old home?" "Yes, dear! It must be very magnificent. Quite like one of the palace homes of the old country. I wonder why Mr. William has never written to us." "Oh! The old house, the dear old cot!" cried Bertha, with an indescribable longing in the tones of her rich, full voice; "I am sick of all this gayety and waste of existence, weary of the world, weary of myself. Well might our friend call these butterflies of fashion, icicles; they freeze, they chill all noble impulses, to coldly cut the soul down to the narrow limits of their own ideas of etiquette and propriety. No trust in the pure instincts that make a women -a true women- shun all vulgarity; no safeguard but the sharp words or cold looks that make their fancied barrier against error. I am sick of it all, and most sick when there is no help for me. Why did he leave us? Why did he guide, counsel, lead me, a wayward child, till my whole life was in his hands, to leave me lonely when I first learned how I loved him?" "You always loved him, Bertha!" said her mother gently, as she stretched out her hand to the excited girl. "Yes, as a child loves her father; but I am a women now, and in the offers I have received, the flattery I have heard since he went away, I have learned a new lesson of my own heart. Learned" -and she knelt down beside her mother, trembling violently, while her voice thrilled with its deep emotion- "learned, mother, how a women loves! He has gone away! He has forgotten me! And I love him!" The golden head drooped low, and the women, humbled by her own frank confession, bent like a child at her motherís knee. Softly the door of the inner room opened wide, and a tall figure came quietly into the room; the stern face lightened with a new hope, the lip smiling at the heartís gladness. "Bertha!" The deep voice thrilled to her very soul, and she sprang to her feet to stand in lowly submission before him. One glance at his face, and , with a cry of joy, she was in his arms, clasped fast to the bosom she loved to rest upon, feeling the strong heart-throbs which told of an emotion too deep for words. At last he spoke, "The old home waits for you, Bertha. The icicles hang from the tall tree you planted, glittering now as brightly as when your baby hands were stretched out to grasp them. Will you come home again, my wife, my Bertha?" And in the upraised face, the deep blue eyes resting so confidingly upon his, he read his answer. Thus it was that the grave, stern teacher won his little "Icicles." Ü

|

|